The above ��before�� and ��after�� photos say it all��a river of blackened sludge used to pour into the Mediterranean Sea, contrasting with, five years later, a clear turquoise sea and clean, sandy beach. For the first time in years, in 2020, Tunisia��s health authorities opened Raoued Beach just north of Tunis for swimming, giving the local economy a boost. Fishermen echoed their approval for the changes they saw in the marine environment.

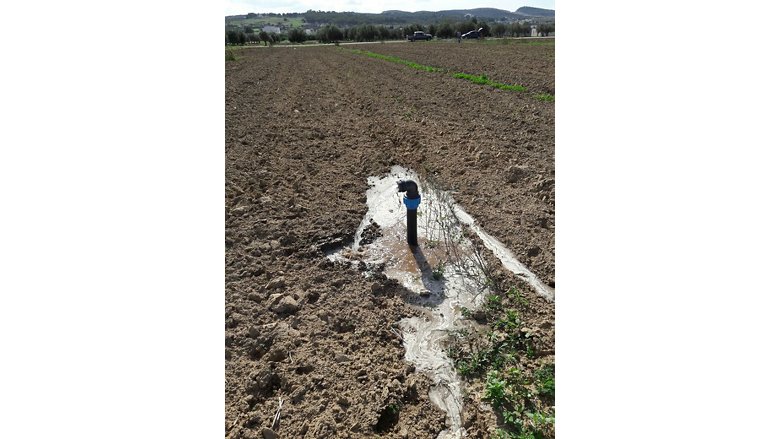

What looks like a miracle was in fact the diligent work of engineers and scientists to clean up the water. 96% of a batch of samples of seawater collected at Raoued in 2020 complied with levels of bacteria considered safe for public health; 97% for the level of detergents. These improvements were the result of channeling treated wastewater underground through pipes to a submarine outfall��the technical term for a pipeline under the sea��stretching 6 kilometers offshore before discharging its effluent 20 meters down the surface. At this depth, farther out in the Gulf of Tunis, treated human sewage and other liquid waste disperses, diluting the pollution associated with daily modern domestic life and farming methods.

Cleaning the wastewater for reuse on land also expands Tunisia��s capacity to adapt to the increasing water scarcity the country has been experiencing as a result of climate change. Investing in a new, environmentally safe system for disposing of treated wastewater preserves the country��s lovely Mediterranean coastline and benefits communities that reside, work, and play along it.

Tunisia is one of the most water scarce countries in the world. In 2017, 367 cubic meters (m3) of water were available per capita to its almost 12 million inhabitants, compared to a regional average of 526 m3 and a global average of 5,700 m3. Urban growth, rising demand, and the need to support employment in rural areas with irrigation, were adding pressure.